By Josh Bookbinder

Luke Weaver was supposed to be here, but he also wasn’t supposed to be here. It doesn’t make sense, but it’s right.

He’s Supposed To Be Here

A decade ago, Weaver was a first-round pick of the Cardinals coming off of incredibly impressive sophomore and junior seasons for the Florida State Seminoles. A year later, he posted a ridiculous 1.62 ERA in A+ ball over almost 100 innings, was named the Cardinals’ minor league pitcher of the year, and climbed the prospect ladder all the way to third on the Cardinals’ preseason 2016 Top 30. He followed it up in the 2016 regular season by torching through Springfield and Memphis in AA and AAA and making his anticipated Major League debut. He was supposed to be here, eight years later, a hero in the postseason and an invaluable piece for a championship roster.

His original 2015 scouting report mentioned a plus fastball, a plus changeup, plus command, and a developing breaking ball that could be molded into two shapes. Pipeline said he would fit in nicely as a #3 starter, which would put him firmly into a playoff rotation for a contending team.

Eight years ago, the future was looking bright. Luke Weaver was supposed to be here, now. Right?

He’s Not Supposed To Be Here

Those eight years in between are why, maybe, he wasn’t.

He got rocked in his first Major League action in 2016. Then he was merely serviceable in 2017, before being awful again in 2018. Finally, the Cardinals dealt him to Arizona in a trade for Paul Goldschmidt.

It almost looked like he had it in Arizona. 2019 was a good year, as he made 12 starts down the stretch and looked very good. There was hope Arizona had fixed something to return Weaver to the solid rotation piece he was supposed to be. Then came the 2020 COVID season.

Minimum 50 IP thanks to the shortened season, he was one of the 5 worst pitchers in baseball by ERA. He led the league in losses, let up almost 11 H/9, and his stuff regressed worse and worse. The Diamondbacks gave him one more shot in 2021 as a reliever, where he was absolutely rocked in 12 appearances before being dumped off to the Royals. Thus began an ugly couple of years, the kind of thing we normally see from a failed prospect.

He was hammered in Kansas City and cut. The Mariners got him, but he never played for them, being cut again before 2023. He was given a shot with the Reds, but after posting a 6.87 ERA in 21 starts, was cut again. The Mariners ran it back, and he paid them back by being teed off on for 12 appearances and cut again.

Finally, the Yankees, in a down year where they missed the playoffs, gave him three starts, and liked what they saw enough to sign him again for 2024.

It’s the type of path that doesn’t inspire confidence. We’ve seen it time and time again: first round pick, big prospect, meteoric rise through the minors, flame out in the majors, and bounce around for a while before calling it a career just beyond the age of 30. So, Weaver wasn’t supposed to be here, just as much as he was.

Where Is Here?

“Here”, as I write, is Luke Weaver, the dominant closer for an ALCS team that is currently up two games to none, and the odds-on favorite to end October as World Series champions. “Here” is articles written about him, people making breakdowns of him, other pitchers trying to emulate him. “Here” is 30 years old, a husband and father of one at thirty years old, looking to repeat his performance next year in a contract year and sign a massive deal to be someone’s relief ace.

That’s “here”. That’s now. It’s a good place to be.

As a die-hard Yankees fan, I’m thrilled for the success of my favorite team, and for the success of a player with an electric arm and an arguably even more electric personality. But as a baseball guy, I’m fascinated with Weaver’s career path, and I want two questions answered: where did it come from, and will he keep it up?

Where Did It Come From?

Short answer: the increasingly-hallowed School Of Matt Blake.

The Yankees pitching coach’s unusual path to the role is well-documented. However, lack of practical experience and big-league pedigree hardly come up anymore. Now, his name is synonymous with making the best out of every arm that comes through the place. Along with Director of Pitching Sam Briend, a Driveline disciple, Blake has turned to tools like The Gas Station to fine-tune pitchers in pinstripes, doing everything from turning rocks to diamonds and making fire from coal (or, even, Cole).

Weaver is one of those many. Off-season tweaks to his arsenal, as well as the new role, have made what we see of Weaver now.

I couldn’t explain it better than the incredible Lance Brozdowski, who broke it all down in a YouTube video. Give it a watch – it’s worth it.

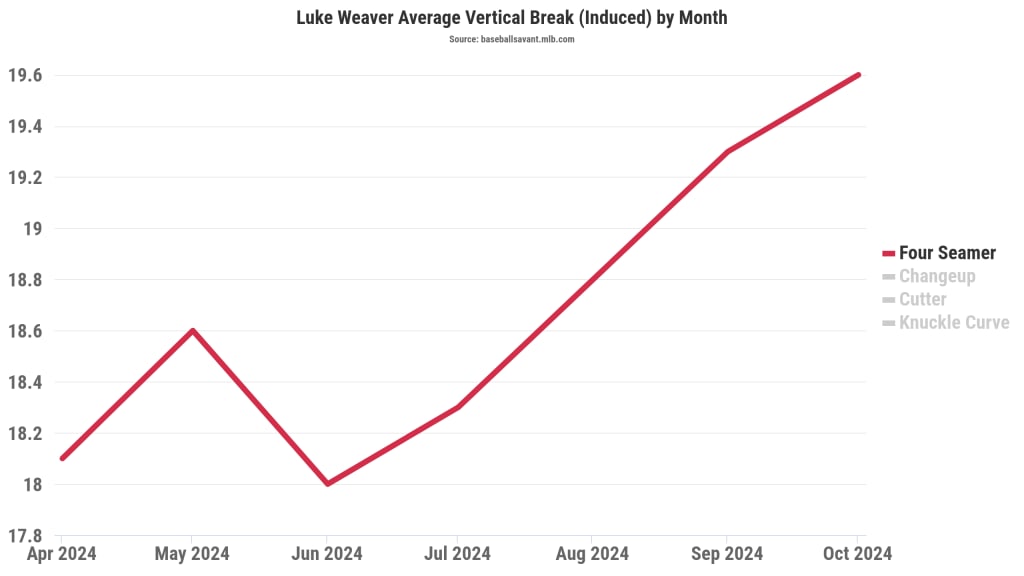

For those without the time, consider the following. Weaver had a dead-average four-seam fastball prior to this year. Changes to his grip have added two mph and three inches of vertical movement to it, making it now an elite riding fastball. Even better, it seems to be improving as the year goes on, peaking at just the right time.

He learned the new grip from maybe the best person you could possibly learn it from: his teammate, the ever-amazing Gerrit Cole. Cole’s fastball is famously ride-based as well, and Weaver’s seems to parallel it in terms of movement. If it isn’t heresy to say, Weaver’s seems to even be better:

| Velocity (mph) | Vertical (in) | Horizontal (in) | |

| Weaver | 95.7 | 18.6 | 6.4 |

| Cole | 95.9 | 17.0 | 6.6 |

In his original scouting report a decade ago, Weaver’s best secondary offering was his fading changeup, and that hasn’t changed. However, he still took steps to improve it to another level.

Another adjusted grip has killed over three inches of vertical movement while retaining nearly the same horizontal movement, creating a vertical separation of just over 14 inches between the fastball and changeup. Combined with a 7 mph velocity change, the combination has become devastating.

Complemented by a solid cutter that became his primary supination-based glove-side break pitch in 2023, Weaver now has a complete arsenal that is more than disgusting enough to give some validity to his breakout.

From the beginning, Weaver was praised for his poise, competitiveness, and command. That’s only flourished even more out of the ‘pen. He has limited his walks to an acceptable level as well as limited home runs (a common issue for ride-based fastball-heavy pitchers) by ensuring his misses don’t miss in a hittable location very often. All numbers from this section from BaseballSavant.

When the Yankees finally (mercifully, some might add) took Clay Holmes out of their closer role, Weaver had the first crack at it. And my goodness, did he deliver. Here were his regular-season numbers since being soft-launched as the closer on September 6th:

| IP | H | BB | ER | K | HR | ERA | WHIP | |

| Stats | 11 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 24 | 0 | 0.00 | 0.64 |

Should we add his postseason numbers up until today, 10/17? I think we should:

| IP | H | BB | ER | K | HR | ERA | WHIP | |

| Stats | 18 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 0.50 | 0.61 |

Now we’re just getting silly.

Oh yeah, Weaver has also closed out every single Yankees postseason win thus far – four saves and five games finished.

It’s incredible, and the tangible changes might truly mean we’re seeing the delayed and long-awaited birth of a relief star. But moving forward, what does it mean? Is it all sustainable?

Moving Forward

My heart says yes, both as a Yankees fan and a fan of baseball and underdogs. Luckily, I think my brain also says yes.

If Weaver can keep up this arsenal and command, it’ll be incredibly hard for hitters to catch up. It’ll be fascinating to see if the improvement we’ve seen over the course of the season stays going up, or if it reverts to the start-of-season version. However, barring true regression, even start-of-season Weaver is more than good enough to keep a pace like this going.

One thing that’s particularly interesting to me is role. Weaver’s been shown to be able to handle closing, and my gut tells me that’s what the Yankees will do. However, I’m interested to see if they allow him to regularly do what he’s done this postseason: multi-inning saves.

Weaver’s background as a starter and previous role in 2024 as a bulk reliever mean he’s able to throw more than one inning, and the stuff stays just as good throughout those longer appearances. Historically, great closers did pitch more than one inning, especially in the playoffs, but that has died down in the last decade or two. If I were in charge, I would absolutely love to see Weaver be given the chance to lock down two or games a week going two innings over three games a week at one inning each.

Especially with the Yankees’ ability to develop relievers out of nowhere (and their reluctance to name anyone other than Clay Holmes a closer – they still haven’t technically called Weaver the closer yet), I think it would be fascinating to see games against the Bombers shrunk to seven innings. It’s a powerful tool, it just remains to be seen whether they’re willing to try it.

No matter how Weaver moves forward, I can’t wait to see it. With the increasing ability of pitchers to be effective late into their thirties, if Weaver’s breakout is for real, we could be looking at the emergence of a dominant closer for a few years to come. I, for one, am really hoping that’s the case.

Josh Bookbinder is a writer for and co-founder of LowThreeQuarter. See more of his work and others’ work on the site through the links at the top of the page, or explore another recent article linked below.

What Is Wrong With Jonathan Loáisiga?

Jonathan Loáisiga once showed great promise but has struggled with command and performance since returning from injury. Analyzing his mechanics could reveal paths for improvement and shed light on how players look to improve.

Mike Marshall And The Oddest Cy Young Ever

The article highlights Mike Marshall’s remarkable 1974 season, where he set a record by pitching in 106 games without starting, winning the Cy Young, challenging current relief pitchers’ valuation.

Do Polar Bears Heat Up In The Cold? On The Nature Of MLB Playoffs

The blog post emphasizes the unpredictability of baseball, especially during the playoffs, where human elements often override statistical analysis. It illustrates how teams focus on merely reaching the postseason because anything can happen, underscoring the contrast between regular season metrics and the magic of October, where facts can become irrelevant.

Leave a comment