By Josh Bookbinder

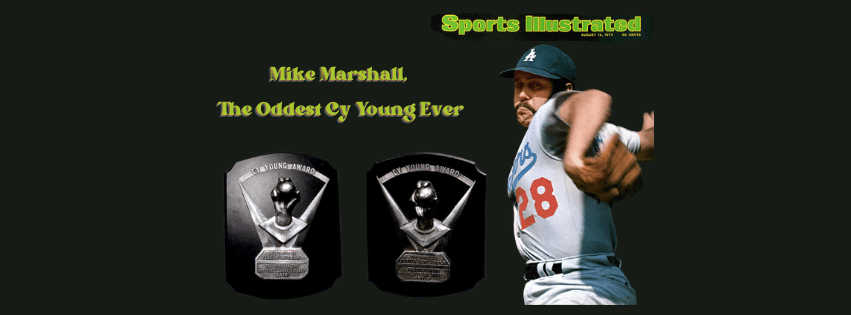

When we think of the Cy Young, we think of dominating performances, unhittable starters, and a pitcher who takes the ball every fifth day and makes the fans buzz with excitement, the word “ace” murmuring through the ballpark. We think of different eras of evaluation and different philosophies, whether that’s pitcher wins, ERA, and WHIP, or WAR, FIP, and strikeouts.

And yet, for one perfectly and beautifully odd season for one of baseball’s under-appreciated greats, none of those things mattered.

Watergate, recessions, and Queen

Let me set the scene: April 8th, 1974. “Hooked On A Feeling” was the number one song on the radio. Blazing Saddles was a hit in cinemas, to which throngs of people wearing funky colors and turtlenecks drove their Ford Pintos, Plymouth Valiants, and Chevy Chevelles. And in the bottom of the 4th inning at Atlanta Stadium, Mike Marshall warmed up for his first relief appearance of the year.

It was Marshall’s first season in Dodger blue after being traded in the off-season from the Montreal Expos, and he was already known throughout the league for being an excellent relief pitcher.

Nowadays, he’s more remembered for his innovative work as a pitching coach, baseball researcher, and doctor, which as of 1974, he had yet to achieve. In fact, prior to this 1974 season, he considered retirement in favor of pursuing his academic goals.

1974 is only six years after the “Year of the Pitcher”, in which Bob Gibson set the modern ERA record of 1.12. Great pitching was being pushed back against, as it had become too dominant; the mound had been lowered, and pitching, while still dominant, was a little more balanced than it had been.

Marshall was all too reminded of this fact as he watched the great Henry Aaron step into the box in the fourth. Aaron’s at-bat would be the most notable part of this April game. It made him the all-time home run king and gave us one of the ultimate highlights in sports history: the irreplaceable Vin Scully, calling the away game in Atlanta, commentating over a color broadcast of Henry Aaron becoming the major league home run champion.

“What a marvelous moment for baseball. What a marvelous moment for Atlanta and the state of Georgia. What a marvelous moment for the country and the world! A Black man is getting a standing ovation in the Deep South for breaking the record of an all-time baseball idol. And it is a great moment for all of us, and particularly for Henry Aaron, who was met at home plate, not only by every member of the Braves but by his father and mother … for the first time in a long time, that poker face of Aaron shows the tremendous strain and relief of what it must have been like to live with for the past several months. It is over! At ten minutes after nine in Atlanta Georgia, Henry Aaron has eclipsed the mark set by Babe Ruth!”

Vin Scully

Tom House, another now-great for his coaching prowess, caught the ball in the Braves bullpen beyond left-center field, and a wonderful celebration ensued. It was a moment that could not be described better than in Scully’s immortal monologue, and marked a point in not just baseball history, but the history of American social culture. The congratulations lasted for a lengthy few minutes, but eventually, everyone realized that there was at least another five innings to finish, despite the early-season matchup likely feeling a little inconsequential in the face of what everyone had just witnessed.

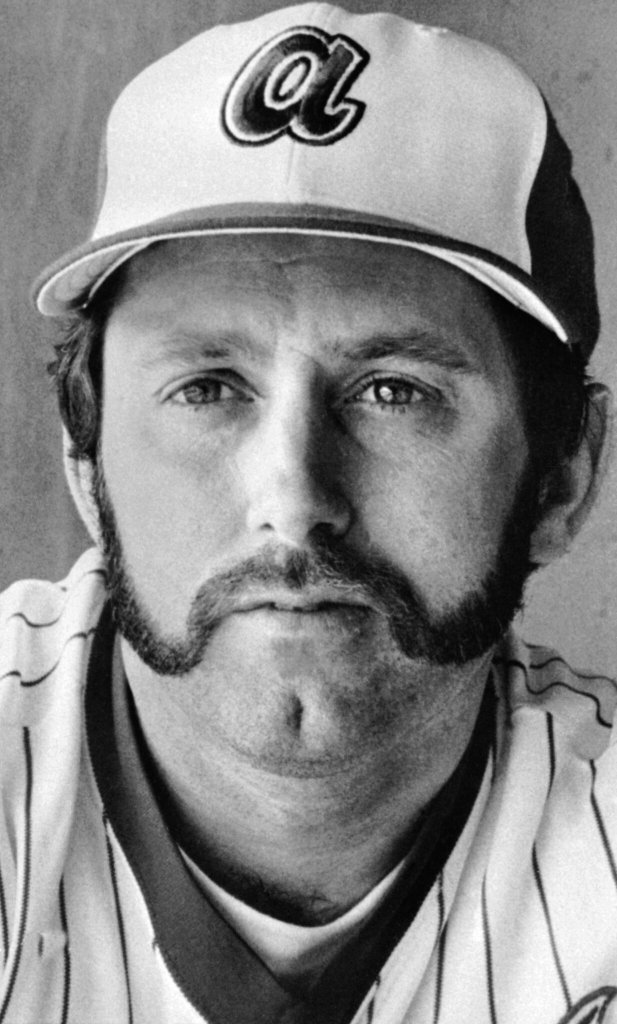

That delay certainly didn’t help Dodger starter Al Downing. Two walks later, Mike Marshall (and his incredible facial hair) entered the ball game for the first time in 1974. Although one of baseball’s great records fell that day, it was the start of another record that still holds to this day, unlike Aaron’s, which was broken by Barry Bonds some thirty years later.

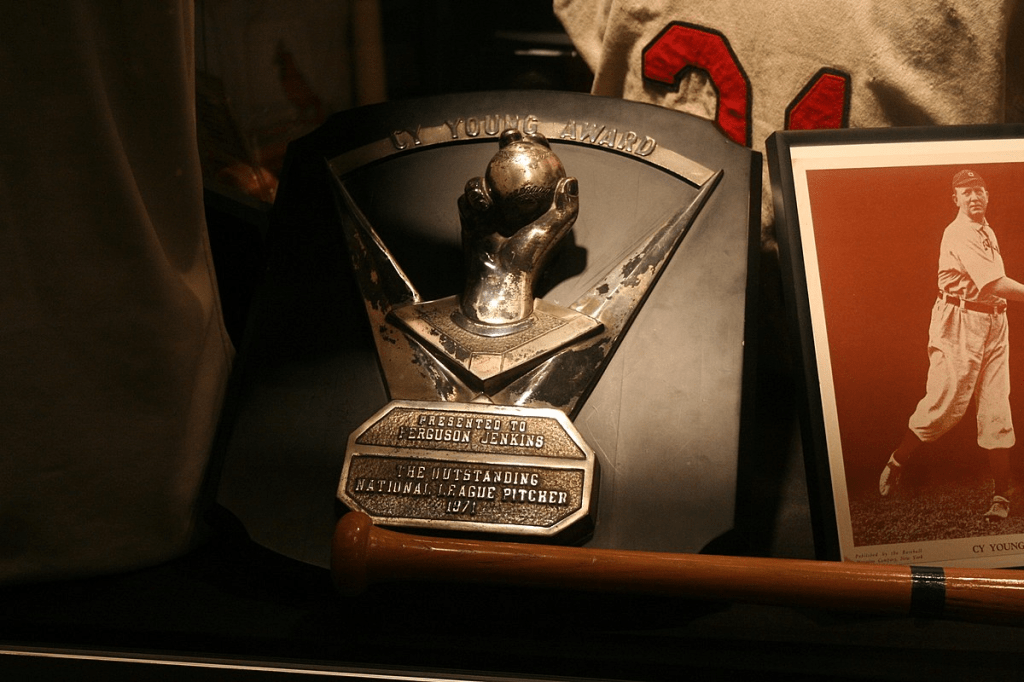

What record am I referencing, you might ask? One of longevity, stamina, and likely a lot of painkillers; Mike Marshall pitched in an incredible 106 games over the course of 1974, starting exactly zero of them. He would throw over 200 innings in those appearances, holding opposing teams to a 2.42 ERA (141 ERA+), and ultimately would win one of the strangest Cy Youngs of all time.

One Hundred and Six

Marshall’s games pitched number is mind-blowing. Out of 162 games, Marshall took the ball for 65% of them. Marshall got four days of rest one time, and appeared on back-to-back games a staggering 53 times. He also appeared in both games of a double-header on July 6th, netting two saves against his former team, the Expos. He helped the Dodgers win 102 games, then threw in 7 out of the 9 postseason games the Dodgers played en route to an NL pennant and a World Series loss to the Oakland Athletics.

This wasn’t, however, entirely unexpected. When he appeared in his 93rd game on September 8th in Cincinnati, he broke the single-season appearances record, held by… Mike Marshall himself. He had set the high watermark the year before with 179 IP in 92 appearances for Montreal. However, the staggering 106 number, upped to 113 when combined with the postseason, was certainly not on anyone’s mind. If you went to a Dodgers regular or postseason game in 1974, you had a 66% chance of seeing the future Dr. Marshall pitch. With his three degrees from Michigan State, I wonder where this accomplishment ranks on his personal ledger; to us, it is simply incredible.

The Cy Young Race

While pitching had been forcibly declined by the league since ’68, there was no shortage of great pitching in the National League six years later. Dodger teammate Andy Messersmith won 20 games (important at that time) and put up a 2.59 ERA (132 ERA+) in 292 innings. Knuckleballing Hall of Famer Phil Niekro dominated for Atlanta, earning 7.1 WAR in 302.1 innings while holding opponents to a 2.38 ERA in 18 complete games. (Niekro never did win a Cy Young, despite regularly leading the league in innings and winning 318 games in his career while accruing 95 WAR). Another Brave, Buzz Capra, led the league in ERA and ERA+ with a 2.28 and 166 and racked up 5.4 WAR, albeit in a “paltry” 217 innings (which would have led the league in 5 out of the 8 most recent MLB seasons as of writing). Even other relievers put up stellar seasons, such as the great “Mad Hungarian” Al Hrabosky, who had a 2.95 ERA in 88 innings.

Ultimately, however, it wasn’t close. Marshall ran away with the award, receiving 96 of the voting points to second place Messersmith’s 66, and picking up 17 of the 24 first-place votes. Niekro finished third, while Capra and Hrabosky finished ninth and fifth respectively.

It’s something unheard of in today’s game. Relievers just don’t win these kinds of things. We’re coming off of one of the greatest relief appearances of all time in Emmanuel Clase’s 2024, whose 4.5 WAR tops Marshall’s 3.1 and whose 0.61 ERA (a laughable 674 ERA+) has earned him all of likely a top 5 finish in the Cy Young. His betting odds currently don’t give him much of a chance at all at winning the award, but it is true that it is yet to be decided.

The last time a reliever won a Cy Young was in 2002, when Eric Gagne ran away with the honor. Since then, 8 relievers have had seasons with an ERA under 1.00, and exactly zero have won the Cy Young. Names like Kimbrel, Britton, Lidge, and Trienen have come and gone without the honor to their name. Perhaps the greatest reliever of all time, Mariano Rivera, had 8 seasons under 2.00, 402 saves, and over 700 innings pitched from 2003 until his retirement before the 2014 season, and he got Cy Young votes only four of those seasons.

So What?

What can we do with this? What are our conclusions?

I think one, we have to reevaluate WAR when it comes to relief pitchers. Marshall was worth a hell of a lot more than 3 wins for that Dodgers team. Great closers shrink the game to eight or sometimes even seven innings; that’s worth more than the stat allows. Great bulk relievers like Marshall, a role that in my opinion is sorely undervalued, rarely get recognition at all. This is especially true depending on the WAR you use; have lower strikeout rates, which hurts their fWAR more than bWAR.

WAR is an awesome stat. It’s a simple and convenient catch-all that allows us to boil a player’s contribution to a single number. But I don’t think it’s perfect, and this is example A.

Another similar takeaway is that bulk relievers may need to make a comeback. 2024 was the year of the elbow, more than ever before. Discourse reigned about arm injuries, velocity, and intent. No one seems to know the answer.

It’s been suggested that workloads need to decrease. Sure, makes sense. Do the thing that hurts you less, spread the work around. But it isn’t realistic or profitable (in terms of wins) to do this in the current fashion of one-inning fireballers.

The Guardians stellar season ended in a series loss to the Yankees, 4-1.

The Cleveland Guardians flamed out in the ALCS this season. They largely relied on an excellent bullpen, including Clase, to anchor them. Cade Smith, Tim Herrin, Hunter Gaddis, and Clase all threw in over 70 games and had sub-2 ERA’s for Cleveland, largely in 1-inning roles; their contributions made up 20.3% of the team’s innings pitched this season. All four struggled mightily in the postseason.

This could be attributed to plenty of things, but I think the reality is that fatigue happens, and one-inning pitchers don’t have the longevity we think they do from limiting their workload. There’s research that shows that the difference between 20 pitches and 50 pitches in a game truly isn’t all that great; maybe we allow these arms who are so effective in 3-4 batter samples to extend to 8-9, and give them a little more recovery time in between outings.

8Meanwhile, 1974 Marshall, a single pitcher, ate up 14.1% of the 1974 Dodgers’ innings. Maybe that’s not a realistic rate half a century later in modern baseball, but there are lessons to be learned from what Marshall did, as well as other great reliever innings-eaters like Kent Tekulve, notable Pirates sidewinder, who can be seen in the image to the right.

Identifying these guys, I think, is easier than expected. Maybe it’s something funky that proves these players to have a little more stamina at the cost of velocity; Marshall threw a wicked screwball, and Tekulve was a funky submariner. Maybe it’s matchup-related, and some pitchers could mow through lineups on a longer leash. But whatever it is, I think it’s important teams start to consider it.

Data suggests that hitters get significantly better seeing pitchers a second and further a third time. Batting averages raise by somewhere in the neighborhood of 0.20 per time seen; OPS’s by about 0.40. That’s the difference between a .250/.750 hitter the first time seeing a pitcher and a .290/.830 hitter the third time; or, in other words, 2024 Johnathan India the first time through and 2024 Jackson Merrill the third.

This logic is usually applied to starting pitchers, but has yet to be applied the opposite in relievers. Why not let a reliever, who has trained for and built up for 8-9 batters as opposed to 3-4, roll through? The batter-to-batter level stats don’t change much, but the lineup rollover stats do.

Legacy

Dr. Mike Marshall died in May of 2021 at his home in Florida, having contributed more than just a few spectacular statistical seasons to the game of baseball. He was one of the first to do real research into the scourge of pitching injuries that has only increased since his heyday. He’s often cited as the inspiration for many of the new-age training doctrines, from Driveline to the ever-controversial Trevor Bauer. He was a founding member of the Seattle Pilots, and was documented at length in Jim Bouton’s famous Ball Four. He was and is a legend of the game that few tend to remember as much as they should, and his lessons can be and should be learned from in today’s baseball, nearly unrecognizable at times from the speed and grit game of the sixties and seventies.

And, of course, he is a one-time Cy Young winner and major league baseball record holder. On April 8th, 1794, as the ill-fated Nixon administration reigned, Marshall began his journey to inscribing his name in the record books. It shouldn’t soon be forgotten.

Josh Bookbinder is a writer for and co-founder of LowThreeQuarter. See more of his work and others’ work on the site through the links at the top of the page, or explore another recent article linked below.

What Is Wrong With Jonathan Loáisiga?

Jonathan Loáisiga once showed great promise but has struggled with command and performance since returning from injury. Analyzing his mechanics could reveal paths for improvement and shed light on how players look to improve.

Dream Weaver: The Birth Of A Star (Finally)

By Josh Bookbinder Luke Weaver was supposed to be here, but he also wasn’t supposed to be here. It doesn’t make sense, but it’s right. He’s Supposed To Be Here A decade ago, Weaver was a first-round pick of the Cardinals coming off of incredibly impressive sophomore and junior seasons for the Florida State Seminoles.…

Do Polar Bears Heat Up In The Cold? On The Nature Of MLB Playoffs

The blog post emphasizes the unpredictability of baseball, especially during the playoffs, where human elements often override statistical analysis. It illustrates how teams focus on merely reaching the postseason because anything can happen, underscoring the contrast between regular season metrics and the magic of October, where facts can become irrelevant.

Leave a comment