By Josh Bookbinder

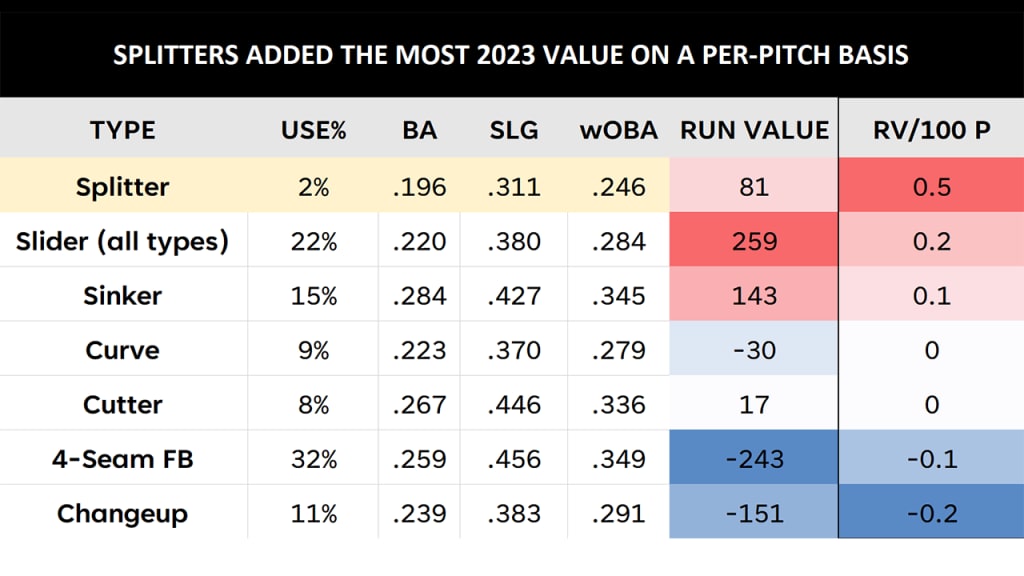

Recently, I had the pleasure of checking out an article by the always-outstanding Mike Petriello for mlb.com about the rise of the splitter. While it’s a great read (and free, go check it out), I walked away completely absorbed in one graphic that Mike included, and not at all for the reason he included it.

Everyone who has had an old-school pitching coach at some point in their lives has heard some variation of “the best off-speed pitch in baseball is a changeup”, or “you’ve gotta have a good changeup to get good hitters out”, or even “you don’t need to throw that [curveball/slider/splitter], it’ll hurt your arm; just throw a changeup, it’s all you need”.

However, according to the graph from Petriello’s article, in the big leagues last year, that literally couldn’t be more wrong. According to BaseballSavant’s Run Value stat, the changeup was in fact the worst pitch in baseball by rate. By a lot.

As a former changeup specialist (example left) who rode the pitch to some pretty cool heights, this hurt my heart, and as a baseball stat nerd, it confounded me. Not only did it not seem to make sense in my old-school pitching brain, but it didn’t make sense in my new-school pitching brain either.

The changeup was always hard to hit, at any level. In some ways, the old heads had always been correct. After all, pitching is just disrupting timing, and nothing does that better than the old bugs bunny string pull. It didn’t make sense, then, that guys were teeing off on the pitch at the highest level.

My baseball history brain churned with images of Pedro Martinez (right), Trevor Hoffman, Tim Lincecum, and Felix Hernandez making All-Stars look like Little Leaguers. Yet, all I kept seeing was that blue box on Mike’s chart: -151 RV. That’s a crazy number.

So, I set to work brainstorming some things and finding some answers to the simple question: what gives? Here’s what I came up with. Oh, and spoiler alert… I don’t think the changeup is dead.

Reason 1: The pitch-tracking era has changed what we call things, and there is a lot of grey area around what a changeup vs a splitter is

Quantify, quantify, quantify. That’s what data has done to baseball, just as we look deeper into the world for more order and more organization. It’s just what we do as humans: the more we like something, the more we want to understand it and put it into boxes.

In pitching, this has meant we need to call pitches different names (slider vs sweeper, anyone?). It has meant we need to decide what everything is; it has meant we can no longer just call a pitch “the thing” (R.A. Dickey reference, for the sickos), but it has to be something. Quantification is king in spaces like modern baseball, as we continue in our endeavor to understand everything there is to understand.

To talk about the changeup, first we have to talk about the splitter, which is an interesting example of the opposite effect within this quantification pursuit. In the past, “splitter” wouldn’t have been a good enough description of a pitch; it used to mean all sorts of things: a split-finger fastball, a split changeup, a forkball, and all sorts of variations in between. Then (as Petriello mentions in his aforementioned article), the splitter fell out of style, with fears of injury risk clouding the sunny excitement of its effectiveness.

Now, since its return (largely thanks to Japanese baseball and their dominance with it, including in the WBC), it’s just been a splitter. All of it. Everything from Jhaon Duran’s 101-mph demon ball to Kutter Crawford‘s floaty forkball thing is just… splitter. What used to be a designation as broad as or broader than “fastball” or “breaking ball” has been reduced to one catch-all name for a whole lot of things. That’s odd for a sport that loves their semantic definition of terms, and it causes some other frustrating issues as well.

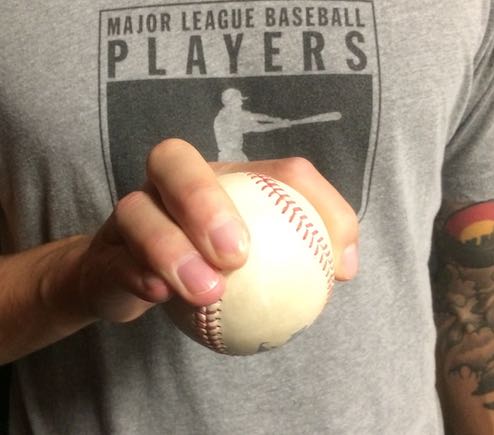

Images from efastball.com, side and top view of a common splitter grip. Note the index and middle finger specifically placed split apart from each other in order to kill spin and velocity, creating a speed separation and tumbling movement pattern.

How does this tangent on splitters and categorization relate to changeups, and the overall idea of quantification in baseball? Here’s my whole thought process:

- As people dive as deep as they can into baseball, they do their best to categorize everything they can.

- Pitches get categorized and changed around to reflect current trends and to try to quantify success more than anything else.

- A good example of this is “slider vs sweeper”; sliders that moved more side-to-side were seemingly performing well, so there was a conscious split between them and they were made into their own thing.

- There’s little separation between a splitter and a changeup, and no one really knows what a splitter is right now.

- Splitters are becoming more popular and successful, so people are inherently biased to categorize more pitches and more pitches that are successful as splitters as opposed to changeups.

Point 4 is bolded there for a reason; I think it’s one of the biggest causes for changeups being valued so poorly right now. While we may crave categorization, there’s really not much difference between a changeup and a splitter, and it’s often just called whatever the pitcher feels like calling it. Let’s take a look at two of the reasons why.

Grips: Gausman, Allen, author, and others

Look at this grip. Look at it. Study it. Stare at it. Tell me what pitch it is.

Changeup, right? You can even see the pointer finger making that signature circle on the side of the ball. Easy-peasy.

Besides, it couldn’t be a splitter There’s hardly a “split” there. This looks like your average straight changeup, probably thrown with some pronation off of the middle finger seam.

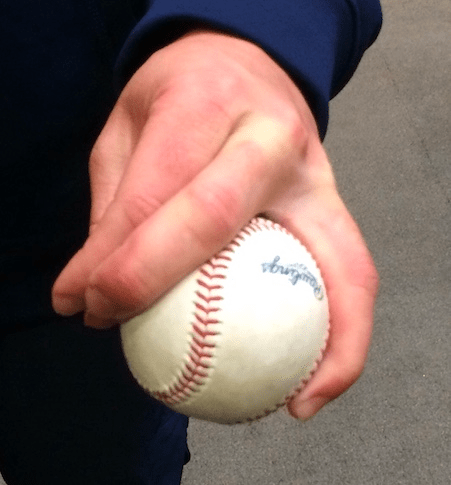

Next, tell me what this grip is, from Logan Allen, formerly a Guardian and now in the Diamondbacks organization.

Nothing says “splitter” like two fingers on complete opposite sides of the ball. He’s using his middle and ring, but it’s certainly a split and a half.

I think it’s pretty fair to call it a splitter, even if it’s not your classic grip. I mean, grab a baseball and try that. It doesn’t feel good. Look at Allen’s hand in the picture. His fingers seem to be calling out for help. Yeah, that’s a split, for sure.

Now that you’ve done all that, click on this youtube video to the right.

Gotcha.

The first picture is Kevin Gausman’s “splitter”, one of the most lauded in the game. It’s been worth +66 RV since 2017 (when RV began being tracked), and is widely considered to be one of the best splitters around anywhere. Logan Allen’s, on the other hand, is a “changeup”, a variation called a vulcan change. Popularized by Eric Gagne and Phil Hughes, it has splitter-like movement, but has never been lumped in with splitters.

Pitchers are fickle creatures. We call things what we think they are, a lot of times just guessing or going off of what “feels right”. Even from an anecdotal side, I threw two different “splitter” variations my final year playing. One was a vulcan change, the other a forkball; neither were a split-fastball. I called them both “splitter”.

Pitchers call their pitches different things for all sorts of reasons, and they’re very often just wrong. Sometimes they’re wrong for a reason; I’ve known pitchers who called a slider a cutter in order to cue them to throw the pitch hard, or called a sinker a four-seam fastball in order to regulate their arm slot and mindset so as to not baby the pitch for movement. However, regardless if it’s for a reason, it’s still wrong; if we’re doing our best to quantify, we cannot simply go off of what pitchers want to call a pitch. It just doesn’t work, and there’s too much nuance and crossover.

But, to be fair, we don’t really do that anyway; in today’s pitch-tracking era, we quantify based off of spin, movement, velocity, and other things less visible to the naked eye (and more concrete, anyway). Using pitch grips is more a reflection of the will of the pitcher than anything else, and is really difficult to use as a reliable metric. Let’s take a look at those.

Pitch metrics: spin, movement, etc

Spin, movement, and velocity are the James, Wade, and Bosh of metrics (the original big three, but maybe not the best anymore and probably need help from others around them to work). Let’s take a look at all three anyway to see if any of them can clue us into a difference that makes sense between changeups and splitters.

Our dataset is this: 375 pitchers recorded 200 batters faced in 2023 and threw a splitter and/or a changeup regularly. Here’s the custom Savant leaderboard, for those interested. What can we see?

Immediately, we can see min/max ranges tell us that there’s overlap between the two pitches:

- Splitters spun between 799-2067 rpm on average, while changeups spun between 894-2683 rpm on average; so the changeup high end was much higher, but the general range was similar with a lot of crossover.

- Splitters were thrown from 81.4 to 98.4 mph on average, while changeups were thrown from 74.6 to 93.2 mph; so changeups were generally thrown softer than splitters, but there is still a ton of crossover between the two in the 80 to 90 mph range.

- Splitters broke anywhere from 2 to 17 inches horizontally, while changeups broke anywhere from 2 to 20 inches horizontally; so there was hardly any difference in how these pitches moved horizontally as a whole.

- Splitters broke downwards with gravity anywhere from 25.3 to 40.3 inches, while changeups moved downwards with gravity anywhere from 21.2 to 47.4 inches downwards with gravity; so the entirety of the splitter vertical movement range is contained within the changeup vertical movement range.

In terms of total averages, it looks like this: (Note: this chart uses IVB, to give both points of comparison; IVB does not use gravity.)

| Splitters | Changeups | |

| Velocity | 86.6 mph | 85.4 mph |

| Spin Rate | 1366 rpm | 1792 rpm |

| Horizontal | 11.2 in RHP 8.1 in LHP* | 14.3 in RHP 14.1 in LHP |

| Vertical (IVB) | 3.2 in | 5.7 in |

*Note: there are very few LHP throwing splitters, which makes this number a wild outlier that can likely be ignored; however, I wanted to note it.

From all of this, we can conclude that changeups are thrown a little softer (but likely negligible) than splitters and can spin more. The movement profiles of the two pitches are very similar, with and most pitches are a case to case basis.

Arm/hand movement: how the pitch is thrown

Another difference in the pitches is in how they’re thrown, but that difference might be smaller than you’d think. A splitter is pretty straightforward, but a changeup can create movement in a couple of ways.

On a changeup, one way is simply allowing the grip to work: this is typically used in circle changes, straight changes, or vulcan changes. This type of changeup tends to kill spin in one way or another, and naturally creates pronation without active effort from the athlete. Some changeups in this vein rely on hand friction through ball contact to slow the ball down and/or kill spin.

Another is a pronation change, like Devin Williams’ famous Airbender. In this case, the athlete rolls the wrist forward, almost screwball-esqe, in order to create spin instead of kill it. These tend to be sharper-moving changeups and are the least

Meanwhile, a splitter tends to be more like the straight change mindset, but to the max. Usually, one would want to kill extreme amounts of spin to cause a sharp downward angle in the movement of the pitch, especially when thrown to primarily be an off-speed pitch. This can be seen in a pitch like Kodai Senga’s ghost fork, seen to the left.

When thrown to be more of a fastball, the same principles still apply, but to a lesser extent. That’s more like Jhoan Duran’s “splinker”, which sits around 97-100 and spins at 1700 rpm. It’s one of the more popular examples of a changeup thanks to its ability to regularly go viral, and thanks to Duran’s superhuman velocity ability that makes a 100-mph pitch an “off-speed pitch”.

There’s an old joke in trading prospects for an established star that goes something like this. One scout doesn’t want to trade the prospects for a star; let’s call him Shmookie Betts. The conversation goes like this:

GM: We need to go get Shmookie Betts. He’s a star, and we need one right away.

Scout: …but these prospects could be anything! They could even be Shmookie Betts!

Herein lies the biggest issue with trying to use how a pitch is thrown to quantify which pitch it actually is:

Player: I throw a bad changeup, so I’m going to try a splitter. How do I do it?

Evaluator: A splitter can really be anything. It can even be a changeup!

So what does this mean?

This all just means it is damn hard to quantify the difference between a changeup and a splitter. As Petriello’s article discusses, the allure of a splitter is usually due to the sharper vertical drop movement pattern and the fact that it’s easier to teach to an established arm. However, I wonder how many examples of these pitches are just “slider/sweeper debate” v2: two pitches thrown similarly, and those that move in a certain way that is in vogue given precedent as the preferred type, since players call pitches whatever they want, really. In this case, pitches that move more sharply and more downward called splitters, and pitches that are more gradual or horizontal called changeups.

This would help to start to explain why changeups performed so poorly. If splitters are the new cool thing and everyone is trying to find a way to throw one, then splitters that would have been classified as changeups in the past might be getting placed in that different bucket now, boosting those RVs and leaving only the bad changeups to pull down the changeup RVs.

Reason 2: It’s really hard to throw a good changeup, and harder to throw them at max effort and as a supination-bias mover

Gas, gas, gas

This guy knows velocity is king.

Velocity is king. It always was, from Walter Johnson to Smoky Joe Wood to Bob Feller to Nolan Ryan to JR Richard to Roger Clemens. But in the pitch-tracking era, velocity has become even more “number one”, to the bemoaning and groaning of old-school Greg Maddux enjoyers (Note: Greg Maddux is my personal favorite pitcher of all time, but let’s be real: he threw with above average velocity for his time in his prime).

It only makes sense, then, that pitchers are in pursuit of throwing harder, and thanks to a lot of metrics that tell us that “throwing harder = good” (no duh), lots of research is in coaching increased velocity… sometimes, even if it means losing finesse.

Plenty of studies have been done into the effects of this pursuit, whether injury-related or performance-related. But something we know for certain is that a trade off of some feel for a mph or two can be the difference now in having a career in a major league bullpen and having a career in real estate.

Consider Julian Merryweather, whose story was detailed in this 2021 Tom Verducci article. Mid-80s in high school, low 90’s in college, but a very good pitcher. Sells out for velocity, losing some of what made him a solid starter, but gaining what limited him to being a non-prospect. Suddenly, he’s in the big leagues.

Consider Josh Hader, also mentioned in the Verducci article. A two-time all-star from 2017-2020, he hovered around a 2-3 ERA and was an established star. He gained a good bit of velocity in 2021, and suddenly was unhittable, posting a 1.23 ERA for the Brew Crew.

Velocity is king. Step on the gas pedal. It might make or break your career.

But let me tell you, from firsthand experience and the experiences of many who would agree, it is hard to step on the gas pedal and throw a consistent, good changeup.

This is more anectodal than anything else, but most pitchers would agree: a changeup is a feel pitch, best thrown to create a change of pace and fool hitters. Trickery, lies, and deceit. That kind of pitch is really hard to throw when every fiber of your body is optimized for maximum efficiency and effort. The more that pitchers chased an extra gear, the more that feathering the brake to throw a butterfly changeup became difficult.

Many pitchers just chose not to do it. Two-pitch guys out of the bullpen are more normalized than ever, and there’s been an emphasis on just throwing your best pitches. Two electric pitches are preferred to five average ones, and it’s easier to pare focus down to the minimum.

And yet, even with this shift, there was still a need to kill velocity and spin and create a change-of-pace pitch to pair with a sharp breaking ball or cutter.

Enter the splitter.

As the tweet above from Chris Langin from Driveline notes, a splitter doesn’t require feel or manipulation in the movement of the body; it just requires being comfortable with holding the ball weird, and then, well…

No wonder it’s the common choice now; as long as your hand can do it, it’s the mindless way to throw an even more effective changeup. And like I mentioned before, in pitching development, the simple answer is always the best answer: simplify, simplify, simplify. The idiot-proof way to throw a changeup is to split it.

Supination and Domination

As baseball evolves, the way that pitchers choose to get outs has changed. What was once a league dominated by soft contact is now dominated by… well… domination. Just like velocity is king in the world of development, strikeouts are king in the world of stats. And we create strikeouts with razor-tight, sharp-moving breaking balls. Check out this excerpt from Josh Norris’ great article for Baseball America last season on the pitch type shifts happening in MLB:

Beginning in 2019, batters were nearly as likely to see a breaking or offspeed pitch as they were a fastball. That trend has only intensified in the four seasons since, to the point where roughly 47% of pitches thrown thus far in 2023 registered on pitch-tracking systems as two-seam or four-seam fastballs or sinkers.

While all non-fastball pitch types have increased in popularity, one pitch in particular has surpassed the others.

The slider is on a major upswing and has become much more common since 2008, the first season of the pitch-tracking era. This season, sliders are up 8.2 percentage points compared to 15 years ago.

The usage of cutters (+2.8), changeups (+1.0), curveballs (+0.8) and splitters (+0.5) is also up from 2008 levels, but none as dramatically as the slider.

Josh Norris, “The Surge Of The Slider In The Pitch-Tracking Era“

The reason for this is simple: it’s hard to hit breaking pitches, especially breaking pitches moving fast. Sliders and sweepers have high whiff rates, and as pitchers have chased these, they’ve developed a talent for supination over pronation (explanation below); naturally, younger players emulate what they see, and they watch nasty breaking pitches get thrown, and try to copy them.

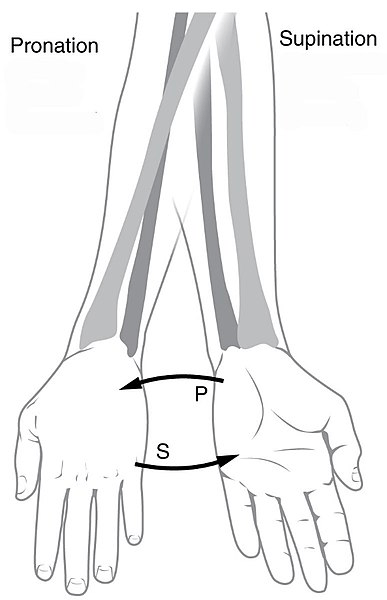

Pronation:

Pronation is turning the hand so that the thumb is down at ball release; how you throw a changeup, sinker, or screwball

Supination:

Supination is turning the hand so that the thumb is up at ball release; how you throw a breaking pitch, like a slider or curveball.

Earlier, we took a look at different types of changeups. Many of those types are thrown using pronation, like the straight changeup and spin-based changeups like Devin Williams’ Airbender. These are also likely the main pitches being tagged as changeups and called changeups because there’s no way to mistake them for splitters. And yet, they require pronation talent, like Langin also mentions in his tweet above. If guys aren’t developing pronation talent, then they’re not going to be able to naturally make the movements necessary to throw a good, consistent changeup.

Conclusions & Moving Forward

I don’t think the changeup is dead. I don’t even think it’s dying. I just think that we’re in a position with baseball that sloppy organization and categorization has led us to a point where we don’t know what the line is between “changeup” and “splitter”. The data is skewed towards the splitter because many of the better changeups or hybrids are being called and categorized as splitters.

So what do we do?

I’m a teacher, and we’re always talking about things being “actionable” in education. So, let’s make this actionable. What can we do to better organize us in our relentless quest for understanding?

Here’s my proposal: right now, we have changeups and splitters. Changeups get the short end of the stick unfairly, and splitters are way too broad a definition. So, let’s break it up. Instead of this…

| Splitter |

| Changeup |

…let’s have this:

| Split-Finger Fastball | Splitters that move very fast and don’t kill significant spin; ex: Jhoan Duran’s splinker |

| Split-Changeup | Splitters that are thrown somewhere in the middle of a splitter and a changeup, and use elements of both; ex: Kevin Gausman’s splitter |

| Forkball | Splitters that are on the extreme side of splitting the fingers to kill spin and create downward tumble; ex: Kodai Senga’s ghost fork |

| Spin or Break Changeup | Changeups that use higher spin numbers in order to generate movement; ex: Devin Williams’ airbender |

| Circle, Straight, or Classic Changeup | Changeups that rely on killing spin through hand friction to create natural depth and run; ex: Kyle Hendricks changeup |

This allows us to categorize by something tangible and actionable, and organize into a situation that makes sense. Personally, moving forward, I’ll be doing my best to use these designations more than the classic splitter and changeup. I think it’s better for accurate pitch grading and player evaluation to have a clearer understanding of how a pitch really works compared to true comps.

Without a doubt, the changeup is alive and well. It’s just hiding a little more than it used to.

The top 10 pitches for each type according to BaseballSavant and Run Value have the changeup second only to slider in non-fastballs, both in total value (which is a counting stat, so can be influenced by amount of pitches) and RV/100* (the rate version). It’ll certainly still be paramount in the coming years to ensure that we categorize correctly, but at the very least we know that even current changeups are still useful when thrown well.

This all means that the best changeups are still incredibly effective and valuable, without a doubt, and they can still be a weapon in the use of the hands of a skilled assassin on the mound. Let’s just hope that the continuing arms race in baseball doesn’t force changeups the way of the sword and the bow-and-arrow.

| Pitch Type | Run Value, top 10 | Run Value / 100, top 10 average |

|---|---|---|

| Fastball | 189 | 1.52 |

| Sinker | 161 | 2.26 |

| Slider | 160 | 2.51 |

| Changeup | 136 | 2.33 |

| Curveball | 125 | 2.29 |

| Cutter | 114 | 2.27 |

| Sweeper | 112 | 2.24 |

| Split-Finger | 85 | 2.81/2.24* |

But until that day, enjoy a compilation of some of the best changeups in recent memory, and look forward to more. They’re a thing of beauty.

Leave a reply to George Kirby Player Breakdown – Low Three Quarter Media Cancel reply